VISIONS OF A CITY – IN-BETWEEN SPACES

How does one experience, understand and through that perhaps try to define a city?

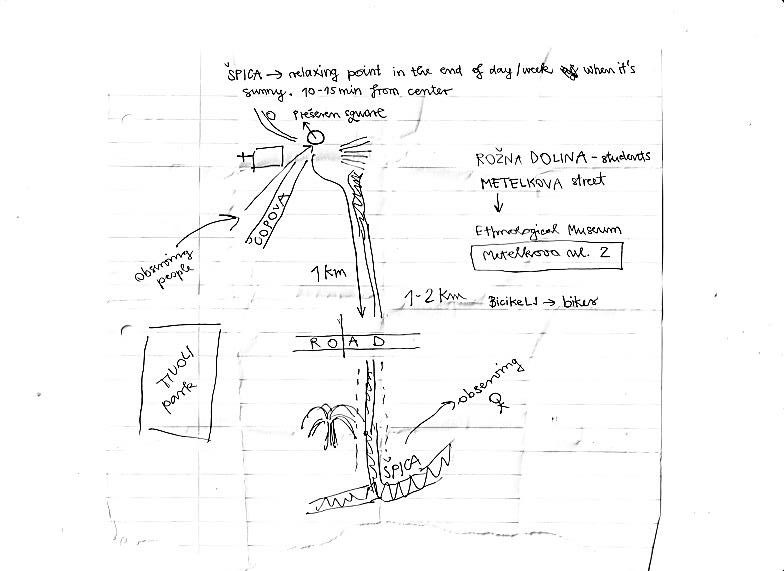

Picture 1: A map of Ljubljana drawn by a student

If the city itself is an ever-changing concept one that evolves day by day, then the starting point for understanding a city must be to look at what defines it. In this essay, I will argue that a crucial aspect of understanding a city, and an often overlooked one, is its space. To look at the parks that the residents are relaxing in, the playgrounds where they go with their children, public squares and green areas. To look at a city’s urban space. Not only to look but to observe. To observe how people interact with the given space, how they use their space, how they transform it and ultimately at what point a space turns into a place. For when talking about people, it is crucial to take space into account, as it is the people that really “make the space”. I will be using Marc Auge’s theories about places and non-places, as well as the ideas of Michel DeCerteau, as a basis and discussion point for exploring the idea of “space becoming a place”. Throughout this essay I will use the words space and place according to my own understanding of how they best apply to the given examples.

In the fieldwork I conducted during a week in Ljubljana, I was faced with a city, which only in recent years has experienced a great increase in interest from around the world. While tourism is not the central concern of this fieldwork, it is crucial to understand the role it plays in how the city positions itself and how so often it finds itself torn between various visions. The visions reveal how Ljubljana wants to present itself, how it should look like and what the “proper aesthetic”, regarding city developing, should be. These visions – ranging from the municipality, to organisations and ultimately to the residents – are then being transferred onto the urban space. This results in spaces that find themselves in-between visions, that is to say, in-between different wishes, hopes and expectations. These spaces are now in-between spaces. Precisely these in-between spaces will be the centre of this fieldwork, where the observation of “urban spaces” will not only include public spaces, but most importantly, the spaces that do not initially fall into this category.

This will be an essay which confronts the idea of what the space of a city theoretically is, and what in reality is accessible to its residents. The focus will be on these in-between spaces along this line of public and fenced of, of predesigned and people-made space. In this essay, I outline three different cases where space constitutes an “in-between” and how these examples relate to city planning.

Picture 2: Space outside “The Library of Things”

This concept of space as an in-between space will include examples of temporal, spatial and aesthetic in-betweens, or of all of the above. By presenting these spaces, or places, I provide an overview of the ideas of this city and its space, which I gathered from interviews with the organisation ProstoRož, a co-founder of the urban gardening project “Beyond a construction site”, a landscape architect, students, strangers, and lastly my own observation. Ultimately through these examples, I will look into the future of city planning and all the questions concerning it. And I want every one of you to ask yourself what your space – your place- in a city is, and what it can be.

CASES OF “IN-BETWEEN”

When considering Ljubljana, it would appear that the city often exists in a spatial in-between. There seems to be some uncertainty as to which spaces and places can be used, what happens to them after some time and what the optimal in-between uses would be. These questions about the “right” usage of space not only constitute a spatial in-between, but a position in-between visions and wishes. All of these aspects then relate to Ljubljana’s space, resulting in the above already mentioned in-between spaces/places. The playground of Savsko Naselje presents the first of three different in-betweens I would like to address in this essay. Firstly, the example of the playground of Savsko Naselje, secondly the Tabor Park and thirdly the Urban Gardening Project “Beyond a construction site”. Finally, I will explore how the “in-between” aspect can also be applied to city development and the future of Ljubljana.

1. NEIGHBOURHOOD RENEWAL IN SAVSKO NASELJE AND ITS PLAYGROUND

What is common good? How can we understand public space?

Taking these questions as a starting point, the Slovenian cultural organisation ProstoRož began their work in Ljubljana. Their role, as they described it to me, was to act as an intermediary between the residents and the municipality.

Their work, as they phrase it, is “exploring public spaces in cities and their meaning for local residents and the society at large” through exhibitions, installations, campaigns and long-term revitalizations. The group of architects and a sociologist started with temporary projects to understand public space and furthermore who the public is that utilises the space.

How does the city function in public spaces? quickly turned into a question of who decides the functions of spaces when the municipality commissioned the group to do a temporary installation in the neighbourhood Savsko Naselje, a former socialist area about a fifteen-minute walk from the city centre. Difficulties arose between the so-called “decision makers”, the municipality, and ProstoRož, when it appeared that the aesthetically pleasing project wasn’t exactly what the overlooked neighbourhood needed. Instead ProstoRož opted for a bottom-up approach, planning a long-term neighbourhood renewal which required close collaboration with the residents.

As ProstoRož described the process of this long-term project to me, they first started by identifying the problems in Savsko Naselje on three levels, namely the spatial, social and economic problems, as well as outlining a communication plan. In order to gain trust and active participation, newspapers were distributed, gatherings were held and, in the end, various groups, consisting of both residents and professionals, transformed the neighbourhood step by step. The question of ownership – a basketball court had seven different owners- and the initial wish of the residents for more parking spaces, posed some problems, however in the end, a few important projects came out of this collaboration. The playground was given a new look, while running tracks planned by the school kids, traffic awareness, garden plots and ultimately “The Library of Things” were all introduced.

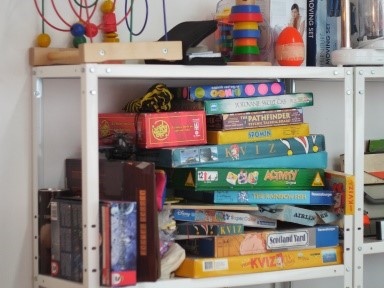

The Library of Things is located in a former community centre, where residents can now borrow “things” from roller-skates to board games. Additionally, the space is available for anyone with interesting ideas on how to use it, which has enabled courses from yoga to dark room film developing to take place. Through these activities, the Library of things has attracted both residents and “outsiders”.

It would appear that this place, where people can borrow useful everyday items and frequent different events, works as a good example in providing a possible set of answers for these questions: How can one make areas more attractive? To whom should they appeal? What actions need to be taken for living areas to become livelier? How does one work best with pre-existing conditions? How can one best support already existing local structures?

In the case of Savsko Naselje, the local structures played a crucial role, since the area already had a community centre, which was required during the socialist times. However, Socialism came to an end in Slovenia in 1990(?) and since then, a lot of former socialist buildings, were no longer used. Since its revitalisation and becoming of the “The Library of Things”, the space has begun to be acknowledged and used by the community again. Despite this being the case, the opening hours were shortened to two days a week, taking away time for more activities to take place. Nevertheless, when visiting the place during its opening hours, not half an hour would go by, without children borrowing roller-skates or residents coming in. From visiting the neighbourhood and hearing different views on the matter, it seemed clear that the project in Savsko managed to bring the residents closer together. This sense of community continues to develop, despite continuing struggles with the municipality on how the future of the playground should look like. This struggle with the municipality seems to be another ongoing theme that overshadows the projects. After the initial enthusiasm and help from the municipality and sponsors, there again seems to be the question of the “in-between”.

Picture 3: Inside “The Library of Things”

What happens now with playground equipment that is too damaged to function well but won’t be replaced by the city? Are opportunities being taken away when the Library of Things has limited opening hours because they are not receiving enough support?

The equipment at the playground in Savsko, specifically a “house” there, which is often frequented by both young residents during the day and older ones after work, slowly falls apart. The wooden floor seems to be rotten and the colour is fading away.

When visiting the playground, the house was still there- there in a temporal in-between. Left over but yet not fully gone. Fittingly enough, the house itself is in-between,. Only the frame of the house is visible. There are no walls or door. Due to this “openness”, the house connects to the nature, while also being damaged by the nature. And yet, this house offers the idea of a safe inside, which is constructed in the children’s minds.

Picture 4: House at playground in Savsko

The municipality, as ProstoRož tells me, knows of this issue but will not repair the house. From the interview it was not clear whether this was due a lack of funds, or just a lack of interest in the project, but from the gathered information it seemed that the municipality moved on to other projects, since they believed that they had at least done “something” in the neighbourhood.. This leaves ProstoRož in a position where they should remove the house to avoid any danger, however, if they remove it, no new equipment will be provided.

The house, the playground, and most importantly the neighbourhood Savsko Naselje as a whole, find themselves in this in-between position in Ljubljana, precisely because the neighbourhood is not an abandoned place, but one that during a long process was revitalised again. However, while the community spirit of the residents has remained,; the outside structure of the project, for example the equipment at the playground, seems to slowly fade again.

Judging from the outside, the circumstances are favourable: there is a large amount of green in the area, a functioning community centre, various empty buildings which could be used, and most importantly a strong community spirit- yet the neighbourhood is still struggling. Ther is a struggle to include what already exists into the vision of the municipality. This is due a lack of acknowledgement and support in areas where structures already exist.

Sometimes it is not only about opening up opportunities but about continuously reinvesting in those that already exist.

Picture 5: Basketball courts in Savsko

Picture 6: Basketball courts in Savsko

2. TABOR PARK

My second example of an in-between space is Tabor Park. It is located a short walk from the city centre, and is found amongst various playgrounds, a hotel, a retirement home and the pristine museums quarter right next to Metelkova – Ljubljana’s alternative quarter. Half of the park consists of a court with basketball hoops used for sports and dancing. The other half is an area in front of a church, where locals take a seat on various benches under the trees. It is both a passageway to reach the museums quarter and a place for spending time and hanging out.

However, in previous years, the park has had quite a negative image. Since it is in private ownership, the municipality did not see the need to invest into the infrastructure of such a place. Hence, the park was neglected and was not being used as much as it could have been.

It took various actions, such as flee-markets and neighbourhood gatherings from various organisations, to make the residents one again- and the municipality for the first time – aware of the park’s potential for the neighbourhood.

Since Ljubljana was elected as the Green Capital of Europe in 2016, there was a strong focus on the green areas of the city. For example, the month of May was given the theme “Green Areas” and because of these events, the municipality finally invested in the infrastructure of the park. The already existing role and function of this park, as a crucial public area in the neighbourhood, was being acknowledged and encouraged.

Through all of this, Tabor park has gained back its identity and is,once once again, an essential meeting point for locals within the quarter.

It is a space that already had the right structures but needed more investment to become properly acknowledged as a park.

Given its central and connecting position, I passed bby the park several times. In the morning, you would find schoolkids running about, elderly people taking a rest, in the afternoon football and basketball matches, until in the early evening the mums with their kids came out to spend some time at the playground. Especially in the corner of Park Tabor, at the children’s playground and the open space in front of the elderly’s home, space truly becomes common good. In this example, space isn’t restricted to its surrounding buildings and their function, but it is open and available to be used by everyone. A buzzing place.

Picture 7: Tabor Park

Picture 8: Tabor Park

Here, the “in-between” aspect is visible in two ways. First and foremost, the space itself is located in-between various important areas, such as the Trubarjeva street and Metelkova. The park serves as a way to connect the surrounding neighbourhoods. . This spatial in-between leads to a common usage of the space as a medium, as a way to connect, both literally and practically. A few years ago, this was the only feature of the park that was used, since, as ProstoRož told me, it simply did not occur to passers-by that the park could also be used for recreational purposes. This was because the park had become quite neglected.

Tabor Park is also an in-between space, judging by the various ways residents, neighbours, and passers-by give use and meaning to the park, ranging from a street/way, to a place to stay and to connect. While the space had always been vital to the quarter, thanks to t its users and its location, outside acknowledgment was needed for the park to reach its full potential.

This example shows that spaces often become well-known places for a large majority of the people through the way they are used. It is only outside recognition that is lacking.

Now even the hotel nearby advertises itself with the green park. Central and connecting as it is, Tabor Park has become the most frequented park in Ljubljana, besides Tivoli Park, and offers the nearby residents a place to relax.

3. BEYOND A CONSTRUCTION SITE

While my first example of an “in-between” was a revitalised, albeit now again slowly deteriorating neighbourhood and my second example a park that reached its full potential only with outside help, the third example is a true in-betweener.

The place that will be discussed here is positioned in-between two ideas, two visions, and two values. It is a spatial in-between, a temporal one and it stands between different ideas of aesthetics and the “right” use of space. Even more so, it is a bridge between the past and the future, and finds itself between the concepts of space and place. It plays with the definition of Marc Auge’s non-places, as “[…] a space which cannot be defined as relational, historical or concerned with identity will be a non-place” (Augé 1995, 78–79), and yet it doesn’t confine to this definition, as I will demonstrate. By not being able to immediately and clearly define the project to one concept, it allows each one of us to question the idea and relation of space and place. The project that all these visions play into is called “Beyond a construction site”, an Urban Gardening project by the Obrat Culture and Art Association together with the Bunker organisation.

Under the context of the cultural festival in 2010, the initiators of this project managed to acquire the permit for an abandoned construction site, which was waiting to be sold and in the meanwhile, was fenced off. Giving both the wishes from the residents for more nature in the city and its perfect predispositions with various trees and useful material laying around, it soon became clear that the optimal use would be an Urban gardening plot. Currently about 40 people, most of them with families, have the key to this garden. All in all, approximately 80 people regularly use the garden, and most of them live in the surrounding buildings. For them, it is a spot of “wilderness” in the city, a place they can form and develop their own ideas. Every so often it also becomes a place for hosting various cultural events, like lectures or film screenings.

Here the following questions are addressed: “Do we need wild places? When does using a space feel natural? Does all space need to be predesigned? How should space be used and by whom?”

Concerning the “natural” use of space, one of the cofounders explained to me that their initial idea was to create “a place for socialising beyond the consumerist notion”. A place where your dog runs around freely and your kids have a slide and a treehouse. It’s also a place of “common good”. Each member of the urban gardening project has their own space, but they also have to look after the common areas, repairing what needs fixing and working together. However, this place is officially only meant to exist in-between the predestined uses. Each year they need to prolong their permit from the municipality, each year they face the danger of being evicted. Here the members find themselves stuck between two visions: what they themselves want to have and what the municipality desires for a newer city. Ironically, as the person I interviewed explained, they feel like they are the “testing rabbits” of the city. Through this project, the city is experimenting both with new forms of space usage as well as justifying their other projects by showing this one off. Seeing how much press coverage they have and how their project truly was a first in Slovenia, it makes me doubt whether at this point the city can actually remove them in the future or whether this temporary use will become permanent.

Picture 9: Beyond the construction site

Picture 10: Beyond the construction site

3.1 SPACE OR PLACE?

Considering all these aspects, how can one now classify this Urban Gardening project? Is it a space? A place? Does it belong to the public or is it priviat? Is it a non-place or is it an elongation of a home?

Trying to find a definite answer proves to be difficult, since once again “Beyond a construction site” places itself in the middle of various definitions. As is often the case, the answer depends on who you ask. In the beginning, the fenced off construction site clearly was private, it belonged – and still does – to the municipality, and the fence prevented any public interest in the space. This resulted in a closed-off space – constituting a non-place since in no way did it offer an identity or a shared reality. However, for me, Marc Auge’s definition of a non-place seems too negative or constricted, for this emerging urban gardening space to also be classified as such.

“If a place can be defined as relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, historical or concerned with identity will be a non-place” (Augé 1995, 78–79).

Yes, “Beyond the Construction Site” does not have a long history in the narrow sense of the word, but the site is connected to narratives, even so shared narratives, it is endowed with meaning, and as such it enables its users to create an identity in relation to this space, which is, at least temporarily, part of their social environment. This identity can be a singular one, if one discovers his or her talent as a gardener for example, or it is a shared identity of all the users, who now work with the same space, under the same conditions and with a majority of the same goals and expectations. Therefore I would describe it as a “place”.

For this project, not only Marc Auge`s concept is worth considering, but also Michel De Certeau, who provides us with a slightly different definition of space and place. He defines “space as a practised place” (DeCertau 1984, p.117). To illustrate this, De Certeau uses the example of a street that through its users becomes a space, an open space. In the case of the Urban Gardening Project, I would argue that this garden is a place because this quote can be reversed, so that the contrary becomes true.

Hence, I would hereby change the above definition from “space as a practised place” to “place as a practised space”. By being used that way, the space changed its identity into a place, which for now remains a temporary one and one that is defined by its users.

A collectively practised space, which through the same narratives and similar ideas of its use and identity becomes a place.

In this collectively practised space, the question of being public or private arises. I argue that this specific case can best be considered a private; however it is one that shows various characteristics of a public space.

Having a key as the requirement for accessing and using the place, clearly is a characteristic of a private good. However, technically speaking, everyone can become a member – and through this process obtain a key- which would possibly make it a public good.

Such a public good, as Chris Webster conceptualizes it, would be a “a collectively consumed good” (Webster 2007,p.82). While this place is in fact collectively consumed, there still is this element of having to be part of the community to really access the property. Therefore, I would argue that the place is still more private than public. While its privacy as such did not change, the garden now has become a public place for locals. This would broaden the definition of a “private good” to one of a of a “local public/shared place” if we take a look at the following description of such.

“A local public good is a collectively consumed good for which demand (usage) falls off with distance […]. They are enjoyed principally or exclusively by those living within a certain area.” (Webster 2007,85).

Since all these characterisations apply to the urban gardening site and the possibility of easily becoming part of the community is given, perhaps the classification as a “shared private local good/place” is the most adequate one.

The key points to take away from this example are that not only the residents give meaning to the place but the garden in fact provides an identity for the city quarter and proves to be a vital green space in the city. As the person I interviewed explained, their main idea behind the project was to create “a place for socialising beyond the consumerist notion”.

“Everything that removes us from social relationships, removes us from a place.” (Auge, cited in Beckerath 1997, p.1 [Transl. JB]). This quote for me sums up both the importance of the project, as well as why this project created a place. It’s about creating a space in which people and their relations are the focus, which in turn makes it a true place.

4. “PROPER AESTHETIC” AND FUTURE CITY DEVELOPMENT

What is an in-between space?

Maria Kramming in her essay about in-between spaces, in German Zwischenräume , classifies them as “gaps that are found within a coherent whole” meaning the city – the structured city- as the whole and the in-between spaces as “gaps” “Kramming 2013, p.1 [Transl. JB]).

She sees them as part of the old structure, either as errors in the city planning or empty spaces that result from the demolishing of buildings. As she mentions however, these “errors” are errors of the past, since current city developments and the planning of such don’t permit these errors anymore. Again, there seems to be this friction between old structures and current processes in the city. This topic of city developments and planning is also very closely linked to the question of “proper aesthetic”.

What is the right aesthetic image that a city should present? Is there such a “right” image? And even more important: “Who decides this?”

A city doesn’t just consist of one vision, one idea about the right image that should be presented and the right way in which a city will represent itself.

Which visions are there? Who’s are they? Which ideas really get considered in the planning and presenting process? And what happens to conflicting visions?

Planning the city means having the power over the vision that in the end will most likely be presented. Here De Certeau says that “[…] city planning is both to give though to the plurality of the real and to make effective that notion of the plural […]” (DeCerteau 1985, p.126) which would be the ideal situation. A situation where the plurality of visions is being considered and included, since planning already means presenting. And deciding for one plan often means excluding another one. Ljubljana’s current situation is much concerned with planning. Planning the city with the right aesthetic in mind. Houses are being renovated, the streets around Ljubljaniza are being re-paved and it quite often seems that the city is striving for “new”. Opinions on this development are varied because multiple factors need to be considered, especially since to a large extent this “refurbishing” has positive consequences for the economy, the living quality and pedestrians.

However, for a majority of people, this vision that the city is trying to realise, seems to be almost too perfect. While a landscape architect recognised the inclusion of Joze Plecnik’s ideas in the planning of the inner city, she feels that slowly but surely the centre is being overdesigned. Do some spaces need to be “ugly”? Can spaces be too pretty? When do spaces not feel natural anymore? How does overdesigning affect the residents and their practises and usage of and in the city? When is a vision too strong?

These are all questions that cities all over the world have to face but it seems that Ljubljana specifically finds itself in an in-between position. The sudden interest of tourists in the city surely puts pressure on the municipality and their hopes for how the city will be viewed. And now the whole city seems to find itself torn between the different visions and directions in which to go. On the one hand, the “ugliness”, the alternative scene that shows itself in the architecture and public spaces, is being promoted and marketed, but on the other hand the municipality has its vision for a newer and better city in mind that focuses on the city centre.

When it comes to neighbourhoods like Savsko Naselje, they are either slowly being renewed and partly shaped in the way that the municipality sees fit, or they are overlooked when the means for refurbishment or constant support is lacking. They tend to forget that often local initiatives or usages of space already exist there. What is the right balance here? Can you support such individual actions and maintain their visions while still modelling the city? Most importantly, is the vision of the municipality an inclusive one? What happens with neglected spaces and can there be a temporary use? If so, what use would be the right one?

Questions like these and many more are currently being discussed. They are not only relevant for Ljubljana and its future but they are also relevant for each one of us. One should ask “For whom is the city?”

As a person I interviewed stated, it’s crucial that the city and its projects, in fact the whole process of designing, are heterogeneous because that is how the society is. And ultimately the city should reflect the society that lives within it.

”We shouldn’t just be the most beautiful city but the most inclusive one”.

All the frictions between the various visions bring us back to the questions “What is public good? How can we understand public space?”

HOW DO WE UNDERSTAND OUR OWN SPACE? HOW DO WE USE IT?

Picture 11: Art from the Museum quarter

PICTURES

Picture 1: A map of Ljubljana drawn by a student

Picture 2: Space outside “The Library of Things” (Jasmin Baumgartner)

Picture 3: Inside “The Library of Things” (Jasmin Baumgartner)

Picture 4: House at playground in Savsko (Jasmin Baumgartner)

Picture 5, 6: Basketball courts in Savsko (Jasmin Baumgartner)

Picture 7, 8: Tabor Park ( Jasmin Baumgartner)

Picture 9, 10: Beyond a construction side (Jasmin Baumgartner)

Picture 11: Art from the Museums quarter (Jasmin Baumgartner)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Augé, Mark (1995), Non-Places. Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso.

DeCertau, Michel (1985), Practises of Space. In: Blonsky, Marhsall (Hrsg.), On signs. Baltimore: JHU Press, pp.123-145.

DeCerteau, Michel (1984), The Practise of Everyday Life. Berkley: University of California Press.

Kramming, Maria (2013), Zwischenräume. Online under:

https://selbstgemachtestadt.wordpress.com/2013/12/22/zwischenraume/ (last seen 16.06.18).

Webster Chris (2007), Property Rights and Private Initatives. In: The Town Planning Review, Vol.78,No.1, 2007, pp.81-101. Online under: http://www.jstore.org/stable/40112703 (last seen 18.05.18).

by Jasmin Baumgartner

Quicklinks

Plattformen

Informationen für

Adresse

Universitätsstraße 65-67

9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee

Austria

+43 463 2700

uni [at] aau [dot] at

www.aau.at

Campus Plan