Tradition vs. Modern Spirit: How Urban Beekeeping Changes the Image of Slovenia

History of Slovenian Beekeeping and Beekeeping Tradition

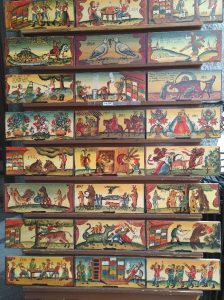

When doing research about beekeeping in Slovenia sooner or later you will stumble upon the Museum of Apiculture in the city of Radovljica, where you can learn everything about the historical use and development of beekeeping in Slovenia. Being investigative researchers, we of course made our way to the museum, which is located in an old Baroque building. So already at this stage you get the feeling that you are entering a very special place which has a long history and tradition that needs to be taken care of and also made aware of. The building itself has a rather nostalgic but at the same time powerful aura to it, and so do the exhibits you can see in the museum which go all the way back to the beginnings of apiculture in Slovenia. The most important thing to acknowledge is that the first attempts to domesticate bees took place in the 7th century, when beekeepers would try to catch swarms of bees and put them into boxes. Many of these practices were not exactly bee-friendly, but in the 18th century one of the biggest names in Slovenian beekeeping history showed up – Anton Janša. He made beekeeping a lot more bee-friendly and was responsible for many changes in beekeeping equipment as well as for writing scientific articles about bees which were proven to be accurate many years later. He is mostly known for creating the Janša beehive, which also contained the famous painted beehive panels.

These paintings found on the beehive panels are an art form of their own, quite often referred to as “folk art”, and they show mostly religious scenes but also scenes taken out of everyday life context and humorous scenes, which are the most recognized ones today. Along with honey these paintings are a popular souvenir for tourists. According to the Museum of Apiculture the paintings represent the cultural height of beekeeping and are Slovenian originals. What is interesting about these paintings is that they could be found around the whole Carniolan area, which at that point of time wasn’t exclusively Slovenian. In Slovenia today, the painted beehive panels are only referred to as being something “typical” of Slovenia, which means they are nationalized and discursively constructed as something Slovenian. Therefore, these beehive panels are an excellent example of how beekeeping functions as an element of a “banal nationalism“.

Alongside the painted beehive panels, what could and still can be found all over Slovenia are apiaries, in which numerous beehives can be fitted. This is the traditional way of Slovenian beekeeping: Having an apiary with beehives inside, taking care of them and, if you are lucky, produce some honey. This traditional form of Slovenian beekeeping is found exclusively in the countryside. And this is also the image that immediately comes to mind when you are thinking of beekeepers. Probably an old man sitting in front of an apiary smoking a pipe and looking over the fields. It is quite an idyllic image, but recently it has changed quite a lot because of new, more modern forms of beekeeping that arise in the city of Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia.

Urban Beekeeping

This new modernized form of beekeeping is called “Urban Beekeeping”. It originated in Paris several years ago and since then it has made its way into other big cities all over the world – New York, Berlin, London and Vienna to name but a few. And now it has also found new ground on the rooftops of Ljubljana because these are the areas where urban beehives ought to be – unused spaces in urban cities, most commonly rooftops that gain a touch of nature and life by putting beehives on them. Apart from this practice, there are many other ways to bring life to unused places – and there are many civil society initiatives which seek to revive and use urban spaces in Ljubljana (see Visions of a City – In-between Spaces).

One of the most famous buildings in Ljubljana that has beehives on its rooftop is the Hotel Park. It is a hotel from the Yugoslav era and is under monument protection, which explains the old-fashioned look of the hotel. If it were not for the big letters saying “Park” in front of the Hotel and the flags of Europe, Slovenia and Ljubljana above the entrance, you probably would not instantly recognise the building as being a hotel. It looks more like a twelve-storied apartment building that is not very eager to attract people, as it is a very simple building with little decoration. As soon as you enter the foyer, this image changes quickly. It seems like a lot of effort was put into the interior appearance of the hotel in order to try and compensate for the almost sad exterior. It is bright, comfortable and modern, which is an interesting resemblance to our beekeeping topic. At first glance beekeeping may seem to be a bit old-fashioned in comparison to the contemporary vision of the city, just like the hotel facade is compared to how it looks inside. Both the hotel and beekeeping are things from the past which still exist today and which remind the people of their history. When you reach the rooftop of the building at the twelfth floor, you are greeted with a very beautiful view over the whole city of Ljubljana. At first, you have to look around for the beehives as they are a little bit hidden in a corner. Apart from the beehives there is not a lot of green on the roof – but we are ensured that there are more plans for the space in the future to make the whole rooftop a green landscape full of nature and life instead of just a plain grey roof. The marketing manager of the hotel told us that there are also classes held up on the roof and sometimes musical events that would be a lot more attractive in a nicer environment rather than the current one. The bees themselves nevertheless seem to be happy with their home at this height, which is of course the most important thing. But what exactly is the point of having beehives up on the roof? There is more than one answer to that question.

The beehives are there to strenghten the image of the Hotel, which describes itself as being “green” and caring for the environment. There are several reasons why urban beekeeping has become more popular over the past few years. Firstly, it is, as the marketing strategy of Hotel Park implies, good for the environment to have more bees in the city to keep the ecological balance stable. Secondly, as we were told by the marketing manager of Hotel Park, urban honey – honey that comes out of urban beehives – is, surprisingly, cleaner and healthier than the honey from the countryside due to the use of pesticides in agriculture that can make their way into the honey and which you will not find in the city. You might say that in return there are more exhaust fumes in the city but in comparison to the pesticides, they are a lot less damaging and also affect the honey less.

So, once you have honey, what can you do with it? The honey that is produced in the beehives of Hotel Park for example is used to make homemade ice-cream and cakes that are sold in the hotel restaurant and it is also given to business partners as a gift. So, the care for the environment may well be one aspect, but what is for sure is that there is also a strong economical value behind these beehives on the Hotel roof.

Changing the Image

There are of course a lot more examples of urban beekeeping than the Hotel Park and they are gaining more and more attention in Ljubljana and also internationally. What is interesting though is how the two visions of traditional and urban beekeeping clash but at the same time want the same things.

On the one side there is the traditional beekeeping in the countryside and the whole representation of cultural heritage and history which comes with it, but which slowly gets overlooked by the new trend of urban beekeeping in the city of Ljubljana. The image that was created as being the “typical Slovenian beekeeping” with the old man sitting in front of an apiary, gets replaced by the modern strategy of putting beehives on rooftops to ensure the health of the city and produce urban honey. The urban-rural divide also implies other differentiations. One urban beekeeper we talked to mentioned that this form of beekeeping is especially popular among younger people and also women. The major difference, however, is the technology that is used. In traditional beekeeping the apiary and the traditional AZ-beehive are common, whereas in urban beekeeping more modern beehives are used which are more suitable for working outdoors. This is where you find the first traditional versus urban clash, as both claim that their technology is better or “the right one”. Nevertheless, the values and the knowledge that are needed to keep bees are the same within both methods. In urban beekeeping as well as in traditional beekeeping the understanding and caring for the bees is essential, as Raffaela Sulzner puts it “a relationship of dependence between beekeeper and bees begins to form, which legitimates interference […] in the beehive”. (Sulzner 2016, p. 191, translation LM) So, apart from different views on the other’s methods, the differences between traditional and urban beekeeping are really not that big when speaking of values and the treatment of the bees. But the change in the representation of the image of Slovenia and the growing importance of urban beekeeping for the international reputation of the country, is quite the opposite to what it used to be according to an urban beekeeper we talked to.

“Because for 100 years the image was this idyllic countryside with a lot of green environment and this beautiful wooden beehouse. And what we are actually doing is clashing with this image. You don’t hear direct complaints, but you sense it, you know. You’re not 100% part of Slovenia, you’re not a real Slovenian beekeeper.”

In that quote you can, on the one hand, feel the existing tension between the traditional and urban beekeepers but, on the other hand, it also shows how craft, lifestyle and national identity blend within the construction of a certain image of “Slovenian beekeeping”, which is currently going through changes. So, what exactly happens to the image of Slovenian beekeeping? Cultural heritage and tradition are no longer at the centre of discussion but instead focus is being put on the environmental issues that Slovenia is trying to raise awareness of by practicing urban beekeeping. The message that stands behind the beehives on the rooftops is something different because it seeks to incorporate environmental and urban questions into the cultural heritage of the country and continue its tradition of beekeeping while proving to be a cosmopolitan state through the practice of urban beekeeping. It is the idea of the city being a perfect and clean environment for bees, a picture that fits for Slovenia – the combination of urban spaces, nature and tradition through beekeeping. A modern form of a local tradition, moving along with the beat of time but still keeping the essentials of the country’s cultural heritage – this is how you could describe the way urban beekeeping changes the image of Slovenia.

Speaking of modernizing old-established structures, you can not only find the attempts to be international and cosmopolitan in beekeeping but also in the education programs at the University of Ljubljana that want to present themselves in the same way – whether it be more or less successfully (see (Guest)-Student?).

Literature

Makarovič, Gorazd (1989), Der Mensch und die Biene: die Apikultur Sloweniens in der traditionellen Wirtschaft und Volkskunst. Begleitveröffentlichung zur Sonderausstellung im Österreichischen Museum für Volkskunde in Wien = Človek in čebela. Ljubljana: Selbstverlag des Slowenischen Ethnographischen Museums.

Sulzner, Raffaela (2016), Von den guten Bienen. Mensch-Tier-Begegnungen in der urbanen Imkerei Wiens. In: Nieradzik, Lukasz/Brigitta Schmidt-Lauber (Hrsg.), Tiere nutzen. Ökonomien tierischer Produktion in der Moderne. Innsbruck et al.: StudienVerlag, p. 183 – 194.

by Lisa Mentzl

Quicklinks

Plattformen

Informationen für

Adresse

Universitätsstraße 65-67

9020 Klagenfurt am Wörthersee

Austria

+43 463 2700

uni [at] aau [dot] at

www.aau.at

Campus Plan